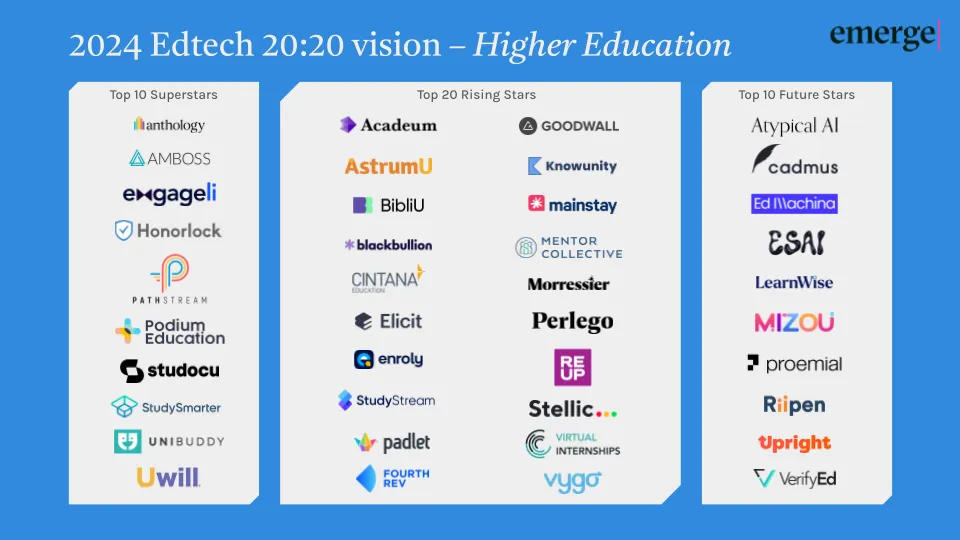

Honorlock, the leading online exam proctoring service, earned a spot as one of the Top 10 Superstars for Higher Education on the 2024 EdTech 20:20 Vision list by Emerge Education.

The list, compiled by Emerge Education with input from industry experts, analyzed over 1,000 companies to highlight the innovative edtech companies that can transform higher education.

Being selected as a Top 10 Superstar means that Honorlock and the other educational technology companies are well-established and well-funded, and each has a large customer base among higher education institutions worldwide.

List Methodology

Emerge Education’s Higher Education Edtech Advisory Board and Venture Partners compile this list through crowdsourcing and voting.

To be considered, companies must meet the following criteria:

- Range and quality of courses/content/teaching methods

- Quality of features and capabilities

- Industry presence, innovation, and influence

- Strength of clients and global reach

- Company size and growth potential

About Honorlock

While most online proctoring services sacrifice the entire test experience to catch cheating, Honorlock is different.

Our smarter proctoring approach combines AI and live human proctors to improve the testing experience for instructors and students while still protecting academic integrity.

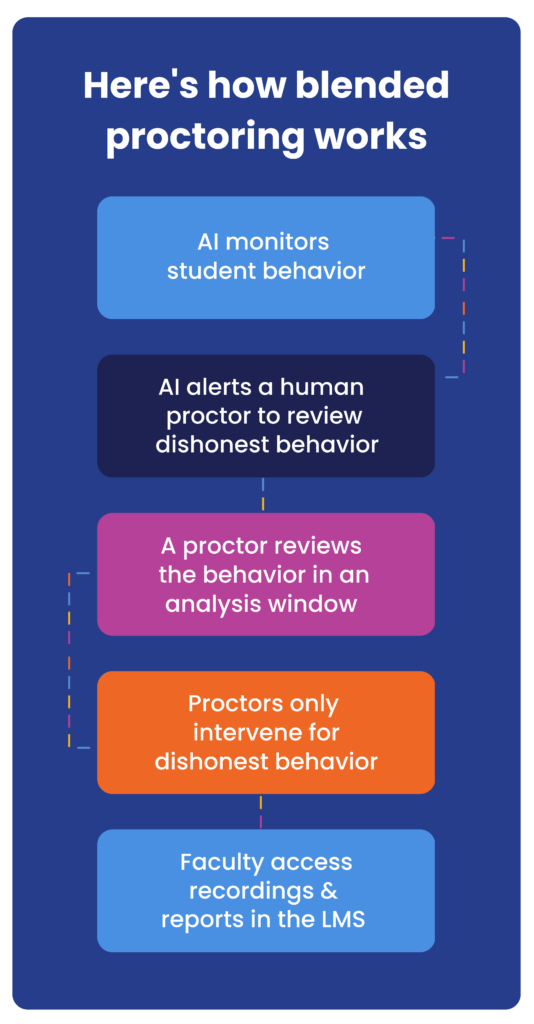

How does Honorlock work?

Pre-exam

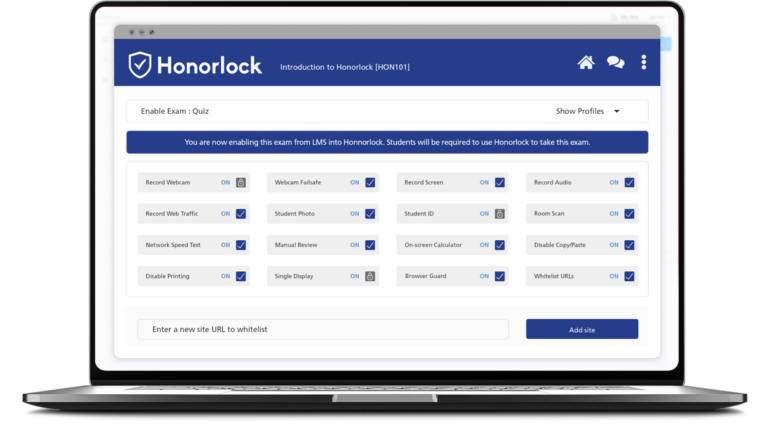

It’s basically the same experience for instructors and students except for a few clicks.

- For instructors: upload your exam to your LMS like you already do, choose which proctoring features you want to use, and set accommodations if needed.

- For students: log into the LMS (no extra passwords/logins), verify ID and scan the room if the instructor requires, and then launch the exam.

During the proctored exam

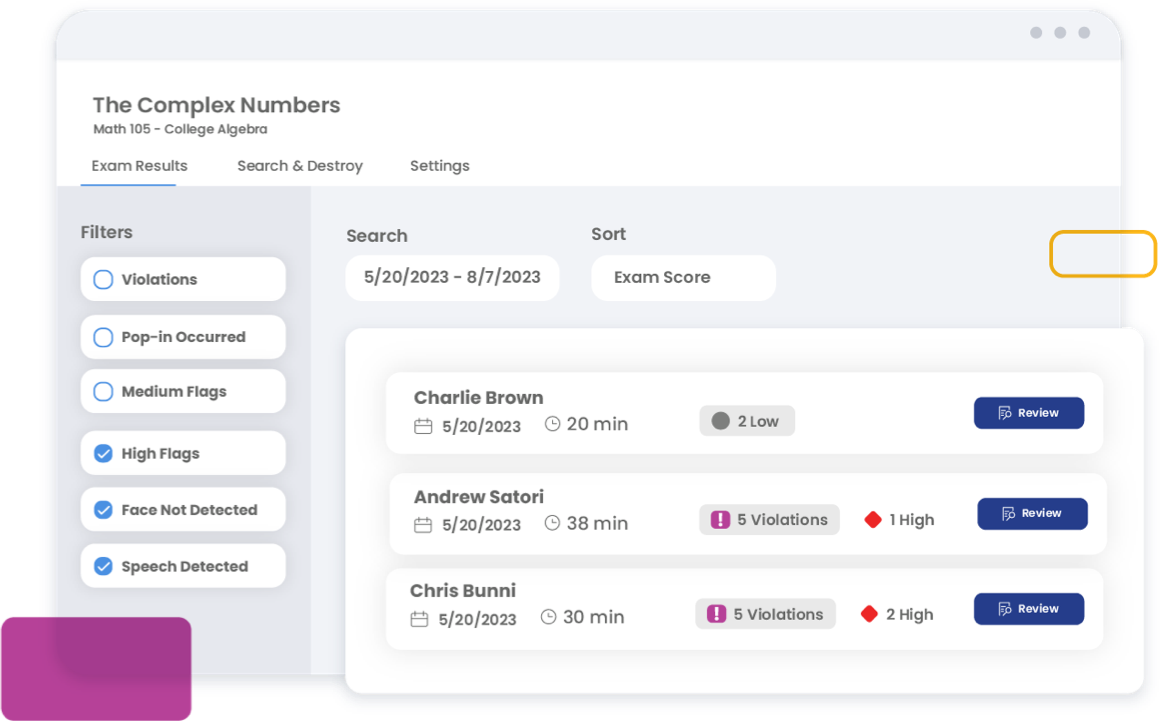

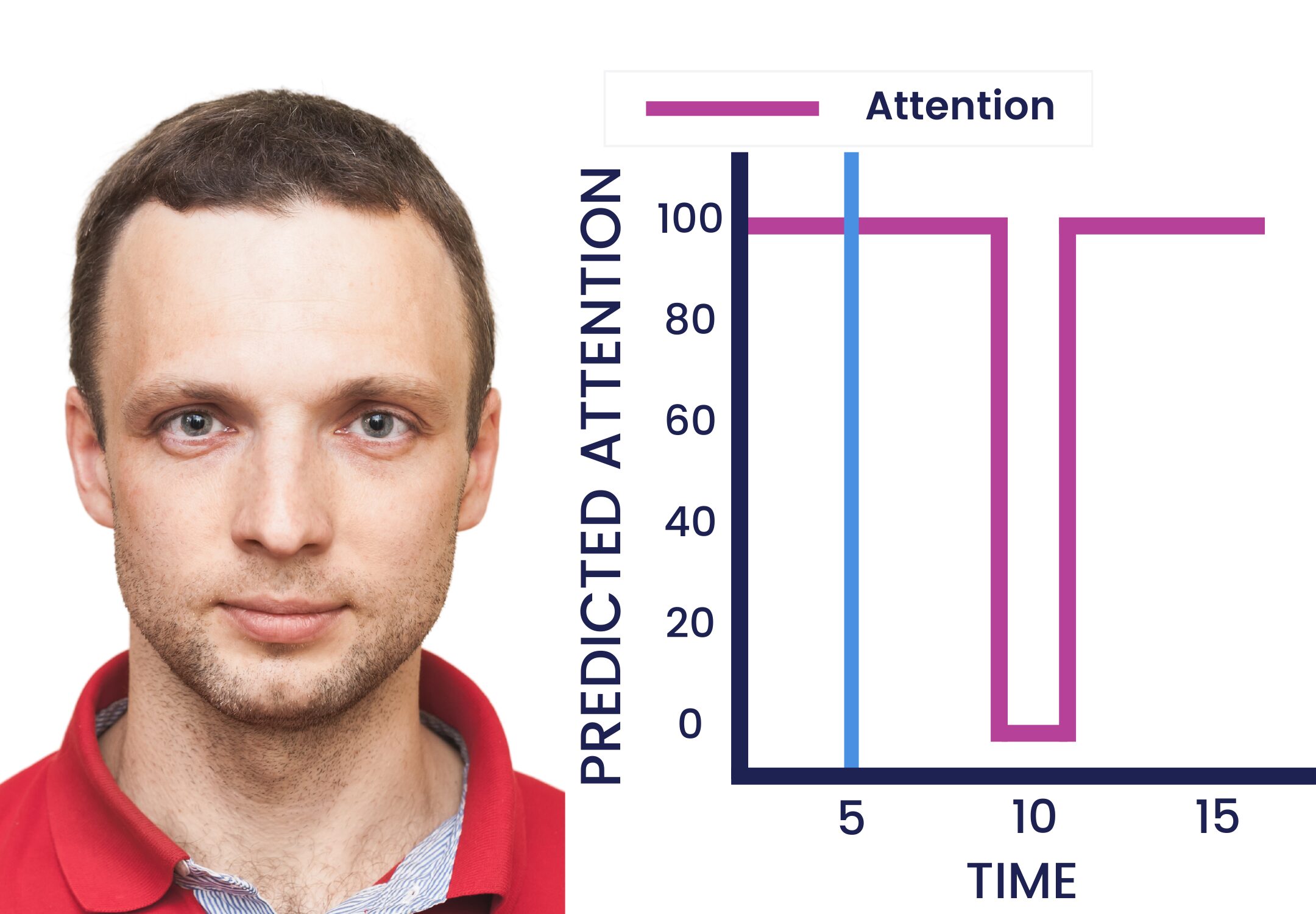

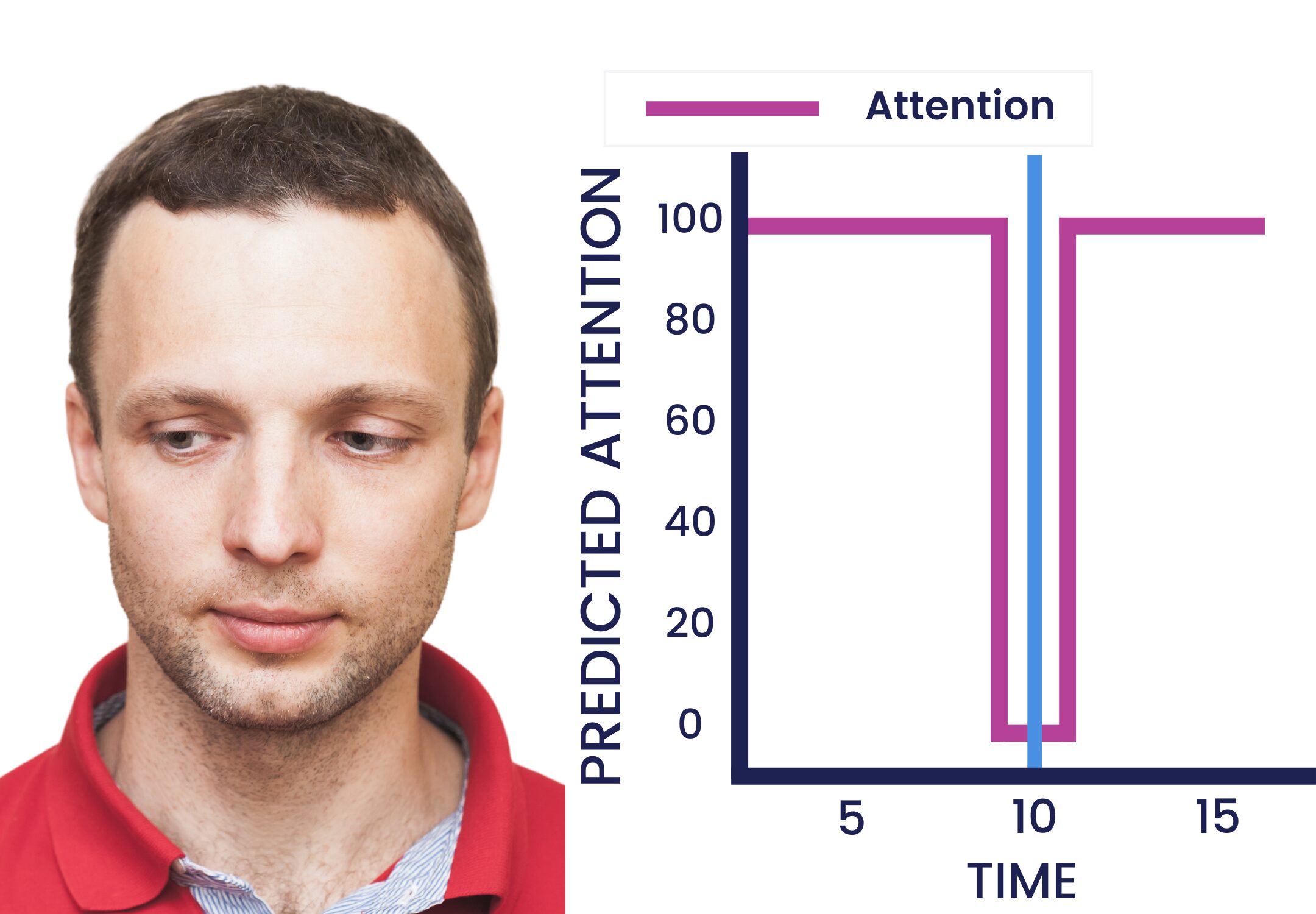

- AI proctoring software monitors each exam session

- If the AI detects potential misconduct, it alerts a live proctor to review the behavior.

- The proctor only intervenes if misconduct occurs. Otherwise, the student won’t be interrupted, and the instructor won’t have to review countless unimportant flags after exams are completed.

Post exam

Because Honorlock’s live proctors review exams in real time, instructors have significantly fewer exam sessions to review.

Additionally, Honorlock offers filterable, easy-to-read reports with timestamped recordings, further streamlining the review process.