13 ways to prevent cheating on online tests:

- Detecting cell phones

- Blocking unauthorized AI chatbots like ChatGPT & Claude

- Catching remote access software in contract cheating

- Finding leaked test questions on the Internet automatically

- Locking the browser down

- Using AI that listens for voice commands to activate voice assistants

- Implementing hybrid virtual proctoring (AI + humans)

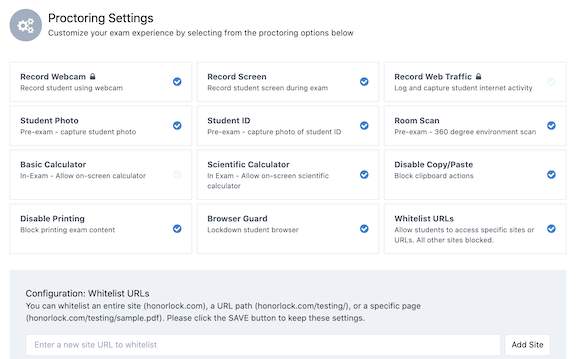

- Verifying ID and monitoring student behavior with a webcam

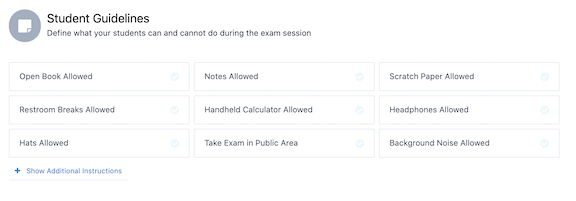

- Creating explicit test rules & instruction

- Reducing test anxiety

- Emphasizing academic integrity and the honor code

- Analyzing reports to identify exam trends that may highlight dishonesty

- Use reporting to identify exam trends that may highlight cheating

Here are 13 ways to stop exam cheating

1. Detect cell phones and other devices

Most people have cell phones or other devices, like smartwatches and laptops, which could be used to look up answers during online exams. In fact, 71% of our proctored exam violations involve cell phones or other secondary devices.

Most proctoring services rely on a proctor to see a phone in real time, which is unreliable when a proctor is watching a nearly dozen test takers at once.

But Honorlock’s cell phone detection technology identifies when test takers attempt to use their phones and other devices to look up answers and when Apple devices are present in the testing area.

2. Block unauthorized AI, like chatbots & browser extensions

ChatGPT, Claude, and Google Bard—all generative AI chatbots—are as controversial in online education as they are popular.

You tell it what to write about and it generates that content in a few seconds. They write pretty well overall, but they can be overly proper and generic sometimes. But with the right instructions, they can write like we (humans) do, and they’re really difficult for AI writing detection software to catch.

How to detect AI writing

Can plagiarism checkers help?

Nope. AI chatbots don’t plagiarize content. They create “fresh” text based on what billions and billions of resources they’ve been trained on.

Do AI writing detection tools work?

Not really. They’re helpful as a high-level gut check, but studies show that AI writing detection tools struggle when the AI-generated text is manually edited with a few small word swaps and paraphrasing. And, as we mentioned earlier, using specific prompts generates human-like content.

Can remote proctoring help?

Yes. Remote proctoring systems can prevent the use of unauthorized AI tools during online exams and even during essays and other written assignments by:

- Blocking access to other browsers and applications so AI tools can’t be used

- Listening for commands that activate voice assistants, which could be used to navigate AI

- Preventing test takers from pasting pre-copied text into exams and assignments

3. Catch remote access software (contract cheating)

Has a technician ever remotely accessed and fixed your computer? That’s remote access software in action.

The downside is that it’s also used for cheating on online exams. The person getting credit pays a service for an expert to secretly take the test for them while they appear on video as if they’re completing the test.

How to block remote access software during online exams:

- Show locations by IP address: Honorlock’s Analytics Hub shows the locations where exams were taken based on IP addresses. If exams are coming from countries without known test takers, this might suggest the use of proxy test-taking services, which may require further investigation.

They could use a VPN to mask their IP address, so you’ll also want to secure your exams from remote access software in other ways.

- Record their screen and require keyboard commands: before the tests or written assignments begin, ask learners to use specific keyboard commands that display all active applications on their device.

- Blocking applications: various settings within Honorlock’s proctoring software can be used to block remote access applications.

4. Use software to find leaked test questions on the internet

Have you Googled your test questions? You should, because they’re often leaked on forums like Reddit, as well as sites that pretend to help with test prep and homework, but they’re really just repositories of test content alongside other avenues of cheating, like their “Expert Q&A” which is just hundreds of their “experts” answering questions 24/7 via chat.

The problem is that searching for your test content takes time… a lot of time.

The good news is that Search & DestroyTM automatically searches the web for your leaked test content in a few minutes and, if it finds any, gives you a one-click option to send a takedown request.

5. Use a browser lock as an initial defense

While browser lockdown software shouldn’t be the only way to secure your exams, it’s a foundational tool to prevent cheating. It secures the test browser by restricting access to other sites and applications and disabling keyboard shortcuts.

6. Detect voices and sounds in the room

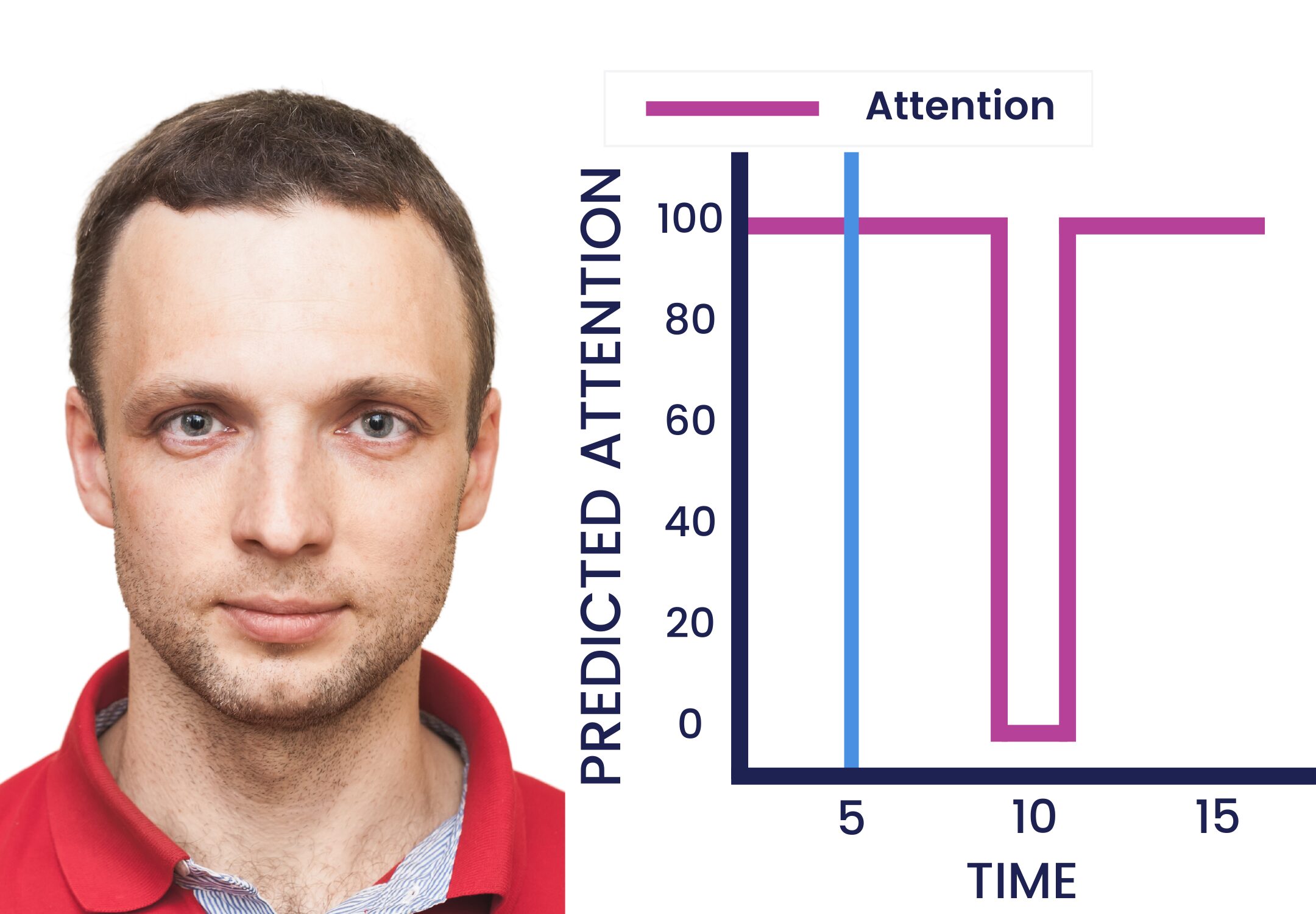

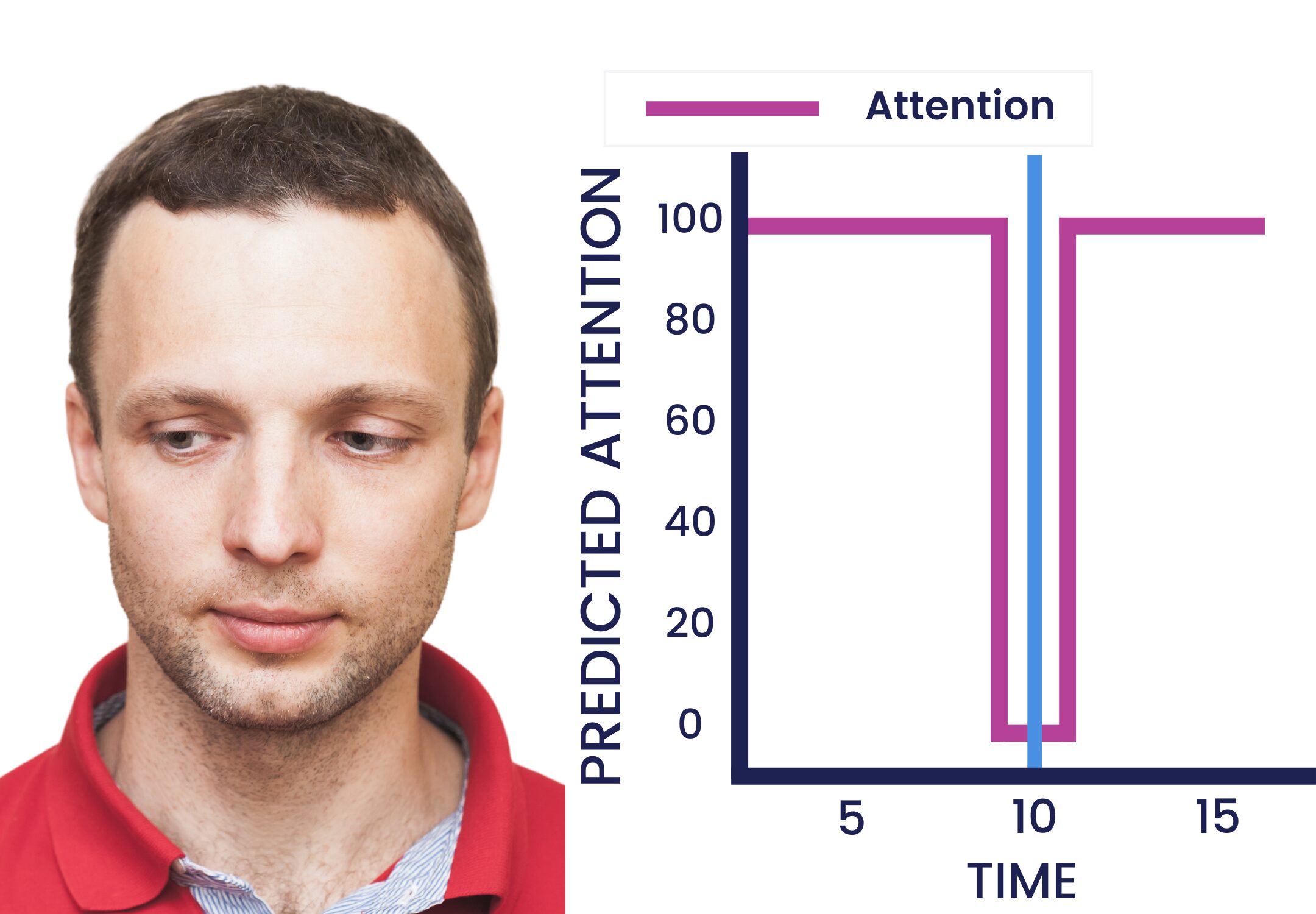

Use voice detection software that listens for specific keywords or phrases that activate voice assistants, such as “Hey Siri” or “OK Google,” to identify test takers who may be attempting to gain an unfair advantage. It then alerts a live remote proctor in real-time to review the situation and intervene if necessary.

This approach to online exam proctoring delivers a much less intimidating and non-invasive testing experience because a proctor will only intervene if the AI detects potential misconduct.

7. Use hybrid virtual proctoring to secure exams

If you’re looking to protect exam integrity, you need a hybrid proctoring solution that combines AI, human review, and a secure browser, rather than just one of those methods.

Honorlock’s hybrid virtual proctoring uses AI to monitor each test taker and alerts a live proctor if potential misconduct is detected. Once alerted, the proctor reviews the situation and intervenes if misconduct actually occurred. If misconduct didn’t occur, the test taker isn’t interrupted. This is a smarter proctoring approach that delivers a much less intimidating and non-invasive testing experience.

8. Use video to monitor behavior and verify ID

Use video proctoring to verify ID, scan the testing room, and monitor student behavior during the exam.

9. Provide explicit rules and clear instructions for your online exams

Writing test rules and instructions can be tricky because they need to be written in a way that removes any ambiguity.

Here’s an example:

- Poor example: Don’t talk to your friends during the assessment.

- Better example: No speaking during all assessments.

Some, while it’s a stretch, may interpret this as, “Well, I can’t ask my friends, but my roommates aren’t my friends, they just live here, so I can talk to them.”

10. Take steps to help reduce test anxiety

It’s important to understand what causes test anxiety before taking steps to help reduce it. A student survey indicated that many feel anxious before an exam because they don’t know what to expect and they have technology concerns.

Two tips to help test anxiety:

- Provide frequent practice tests to help students understand what to expect and ensure that their technology works correctly.

- Use online proctoring software that combines AI with human proctors to help support students during the exam.

Learn more about how to reduce test anxiety using online learning technology.

11. Provide flexibility to take exams 24/7

It’s proven that students are more likely to cheat when they’re tired. Honorlock’s on-demand proctoring services and live support are available 24/7/365 so that even if it’s at 2 am on a holiday weekend, they can take exams when they’re ready. If they feel most alert and prepared at 2:00 a.m., 2:00 a.m. is when they can take the test and get support from a real person in a matter of seconds.

12. Create an honor code and remind learners of the disciplinary procedure

Create your own honor code in addition to the institution’s. Studies show that the act of writing “I pledge that this is my own work,” or something similar, actually helps reduce cheating on exams.

Ensure that test takers know the importance of academic integrity along with what consequences will be enforced for exam misconduct.

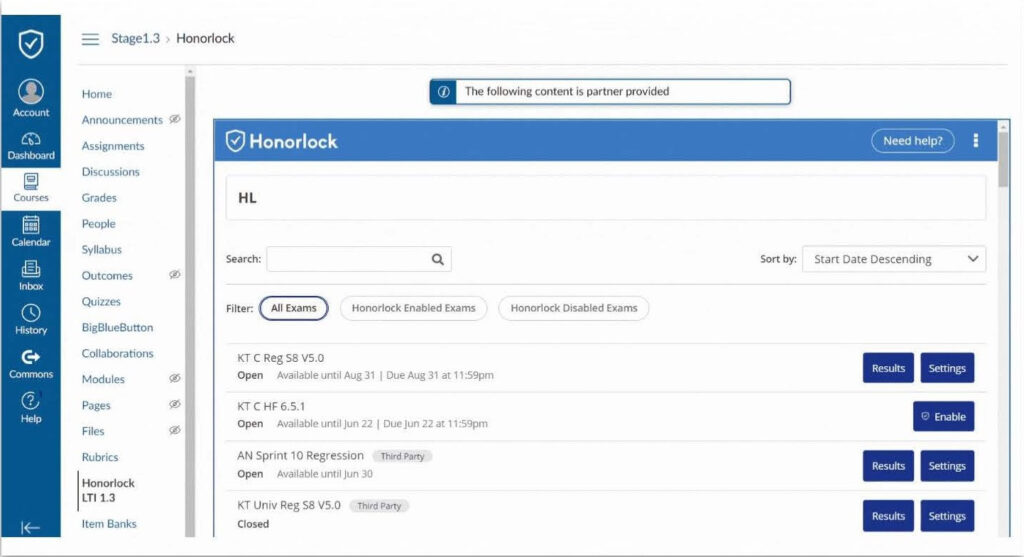

13. Use reporting to identify exam trends that may highlight cheating

Use reporting and recordings from online proctoring software to better understand how students are approaching your exams.

Here’s how a lecturer from the University of Florida used Honorlock to identify trends and anomalies in test scores:

“After the second quiz in the third week of class, I had a ceiling effect that looked like a ski jump, with 80% of my students getting 100% on tests. I knew there was something seriously wrong. I began looking closely at who had missed which questions over the two quizzes. That’s when I realized I needed a proctoring solution of some kind. When I initially attempted to address the issue, I really didn’t even know enough to ask the right questions to get help… Honorlock was more than a tool to guard or block students from using inappropriate information. It was also a means to detect and determine many different ways that students approach the exams.” – Ryan P. Mears, PhD, Lecturer, University of Florida

Honorlock’s online exam proctoring software collects extensive data and provides actionable reports and time-stamped recordings within the LMS dashboard. The exam reports appear in an easy-to-read format that includes relevant student activity such as violations and any suspicious behavior.

Common reasons for cheating on exams

There are many different reasons why people cheat on online exams. Some do it because they can. Others do it because they feel they have to. Here are some of the common reasons behind cheating on exams:

Pressure

Whether it’s a college student who needs to maintain a scholarship or an employee who needs to pass a certification exam to get that salary bump, pressure is a key reason for cheating on exams.

Opportunity

Surveys tell us that people are more likely to cheat on online exams than they are in a classroom or testing center.

Some treat it like that proverbial moment when the teacher has to step out of the classroom during a traditional test, and suddenly, it’s a free-for-all. Many who would otherwise be honest find cheating harder to resist when it seems easy to do without getting caught.

Competitiveness

School and the workplace are competitive for everyone involved. And the desire to outperform others can motivate those who believe they can’t “win” fairly to employ questionable tactics.

Lack of Preparation

Cheating can sometimes result from not feeling prepared for an exam, which may be due to completely normal, valid reasons, such as working long hours, engaging in extracurricular activities, or spending time with family.

Honorlock’s online proctoring services and software prevent cheating on online exams while improving the experience.

Instead of making the testing experience a hassle like most proctoring companies do, Honorlock makes everything easy.

From software that’s extremely easy to use and customize to no exam scheduling and live support that responds in seconds, Honorlock is ready when you are.

Sign up below to receive more resources for tips, best practices, white papers, and industry trends

Want to see Honorlock in action? Schedule a demo.