Consider taking this approach to protecting academic integrity to prevent academic cheating while empowering students.

Considerations on a Punitive versus a Developmental Approach

To say that coronavirus was a major disruption to colleges and universities across the country could not be more of an understatement. Since Spring semester 2020, colleges and universities have been tasked with completely turning their worlds upside down in order to keep students engaged and learning while simultaneously keeping them safe.

More than 1,300 colleges and universities in all 50 states canceled in-person classes and/or switched to online instruction as the pandemic accelerated.1 At least 14 million students have been affected.2

Delivering and consuming instruction was not the only challenge. The pandemic also altered nearly every aspect of college life. Students and faculty made it through canceling events, closing dorms and the demise of all the things that make college life enriching including peer groups, student/faculty dynamics and athletics just to name a few.

As students left campus and online learning increased, institutions also needed to ensure academic integrity for this enormous initiative. Testing paradigms had to shift – and shift quickly. Honorlock alone provided over 6 million online proctored exams in support of higher ed during this time.

Making it through the pandemic

It has been over a year since the pandemic hit. The good news is the undergraduate grades have held steady and even improved at a number of universities that offered most courses remotely.3 That’s something to be proud of, considering all the fear of the unknown and plain hard work it took for faculty and students alike.

But all is well. Beth McMurtrie in “Good Grades, Stressed Students” goes on to say:

“…Averages can hide a lot. Some campuses saw a rise in the number of students on probation or dropping out after a semester, even if average GPAs did not decline. Some campuses reported a significant amount of cheating, which may skew grades and suggest deeper struggles for students.”

Many students struggled to adjust to remote learning

The data also suggests newer students unfamiliar with college life, students on a lower socio-economic scale and students in community colleges fared worse than others. A new report from the National Student Clearinghouse found summer enrollment fell the most at community colleges and among black students.4

In the “Good Grades, Stressed Out Students” article, we meet Jackie Bell, a sophomore at San Francisco State University. All but one of her courses are virtual, so she has spent hours in her bedroom each day without talking to anyone. Other than a 9 a.m. live class three times a week, she watches taped lectures, takes notes, and works on her assignments until 6 pm.

Jackie also had difficulty figuring out her path through college. She met virtually with someone in advising, but later found out they had given her the wrong information. She also tried to make an appointment with a counselor, but they were either too busy or when she did connect, they suffered from technical issues.

“I already don’t know anything about the system,” she said. “Online I have to dig even more. There’s nobody telling me, maybe you should check this out.”

In that same article, Allison Calhoun-Brown, senior vice president for student success and chief enrollment officer at Georgia State University added:

“First-year students just didn’t know how to do college. They didn’t have a sense of where they could get support, how all this works, how to organize yourself well enough to know the deadlines.”

She continued:

“A lot of the best research said that these classes should be taught asynchronously, but we found that students performed much better if the class was synchronous. There was probably a stronger connection to classmates and students.”

One professor at UC-Santa Barbara had students tell him they were expected to help out at home more now than before, cutting into study time. Parents were impacted – if they could keep work at all – with all the childcare challenges that COVID brought, for example. So siblings were expected to pitch in.

COVID created a perfect storm of change and stress, coupled with the need for students to “make the grade” in uncharted territory.

The need for online exam integrity is growing to include non academic settings

As investments in the digital delivery of online learning content increased significantly over the last several months, so too has the focus on administering high-stakes online exams to allow test takers to take such exams from their homes without risking exposure to COVID-19.5

And as important as COVID was in shining the spotlight on academic integrity – for online proctoring, it is quickly becoming even larger than academia alone.

Testing organizations have introduced home-based online versions of exams, such as the Graduate Records Examination (GRE), the Advanced Placement (AP) exams, and the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) exam.

Corporations learned lessons from COVID as well. The remote work phenomenon opened up a new frontier in how and where work gets done, and it has spilled over into how certification paths for workers are delivered and administered.

Certification paths for skills development are on the upswing in corporate America, and it really began to take off as COVID struck. Just as in academia, online proctoring improvements enabled organizations to move from more expensive in person formats and enabled corporations to continue offering certification tracks virtually.

And we will have learned the lessons of COVID (hopefully) in order to apply them to the next pandemic in what has become a global village.

Online proctoring software will continue to improve

So, while we may all wish to debate the privacy concerns with remote proctoring, the reality is, it’s here to stay. At the very least identities need to be verified and abject cheating will need to be flagged, whether you are in an academic setting or a corporate one.

Will online proctoring continue to evolve over time? Most assuredly so. Will it happen fast enough to assuage students who feel they have had this thrust upon them in a very demanding time. Probably not.

What can we do to help students adjust and still protect academic integrity?

So what can we do to help our students adjust to this new testing paradigm? First, we need to consider looking at “cheating” through a bit of a different lens. There are really two different approaches here.

First, rather than look at proctored online testing as a way to “catch” cheaters, consider it a tool for visibility into how and why the academic cheating may be happening.

Secondly, we need to figure out what we should “do” with cheaters and their need to cheat. That’s the harder one.

For these questions, we turn to the work of Tricia Bertram Gallant, who Honorlock had the pleasure of working with at a recent Academic Integrity Online virtual seminar in conjunction with The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Dr. Bertram Gallant is an internationally known expert on integrity and ethics in education. She is a long-time leader with the International Center for Academic Integrity (ICAI). She is also the Director of Academic Integrity at UC San Diego.

In a recent UC San Diego newsletter article, entitled “Does Remote Instruction Make Cheating Easier”6 Dr Bertram Gallant breaks down remote instruction versus online learning in answering the following question:

Is it remote instruction that can increase the chances of students cheating, or more likely the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Unfortunately, we know much less about remote instruction than we do for online learning, which is very different from remote instruction. Online learning is planned, and often exams are still proctored (with either online services or required in-person proctoring).

Remote instruction is the mode of instruction in which students are temporarily separated from the instructor and course content is delivered digitally, as in the case of an emergency campus closure.

We don’t know if students are cheating specifically because of remote instruction. But we do know from the research conducted over the last 10 decades by behavioral economists such as Dan Ariely and psychologists such as Eric Anderman, among others, that human beings are more likely to cheat when:

- They see or believe that other people are doing it.

- There are temptations/opportunities (that is, cheating is situational).

- There is a heightened state of arousal, stress or pressure.

- The class rewards performance rather than mastery of the material.

- The class reinforces extrinsic (i.e., grades), not intrinsic (i.e. learning), goals.

- Instruction is (perceived to be) poor.

- When it’s less likely that there will be costs to cheating.

- They can disassociate their self-identity from their actions.

So, if remote instruction or the pandemic result in any of the above factors, then it is logical to conclude that there would be increased chances of academic cheating.

Consider a developmental approach rather than punishment when cheating occurs

Dr. Bertram Gallant’s work in getting to the bottom of why students cheat and then using the information to help students not cheat is of great interest.

Rather than a simplistic punitive approach “don’t cheat,” Dr. Bertram Gallant’s work revolves around developmental approach examples that use the student’s reasons for cheating and couple them with targeted mentoring based on those reasons to move the student toward a higher integrity stance. She sees this as fundamental to the responsibilities of each institution to the student.

In a recent Journal of College and Character article entitled Punishment is Not Enough, The Moral Imperative to Responding to Cheating With A Developmental Approach7, she writes:

The rates of academic cheating should not surprise us. Deception is used by all species as a strategy for survival and success, and so the act of cheating by students may be seen as a “natural and normal” (Stephens, 2019, p. 9) response to school systems and cultures that value “achievement, credentials, and getting ahead” more than learning (Galloway, 2012, p. 391).

Consider the hypothetical student who is at risk of failing a class, the consequence of which would be losing their financial aid and thus their ability to pay their rent. In such a case, deception, rather than honesty, may be the intuitive, default response of the student, with honesty requiring more deliberative thought and reflection (Bereby-Meyer & Shalvi, 2015).

This intuition toward deception is bolstered by what Ariely (2012) calls the “fudge factor,” our ability to maintain a healthy sense of ourselves as honest people even as we cheat. This “fudge factor” is on full display in the Josephson Institute survey—while half of the students admitted to cheating, 93% of them expressed satisfaction with their own morality.

This is not to say that colleges and universities should accept cheating as morally acceptable or inevitable (Stephens, 2019). Academic cheating is certainly not morally acceptable. When students cheat, even on the most minor of assessments, they are being dishonest (i.e., misrepresenting that they know, have done, and/or can do) and perpetuating unfairness (i.e., gaining a competitive advantage over those who have been honest).

As such, cheating represents an existential threat to academia because it not only undermines student learning (both academic and moral) but also the validity of its assessment and, ultimately, the integrity of the credentials conferred upon them.

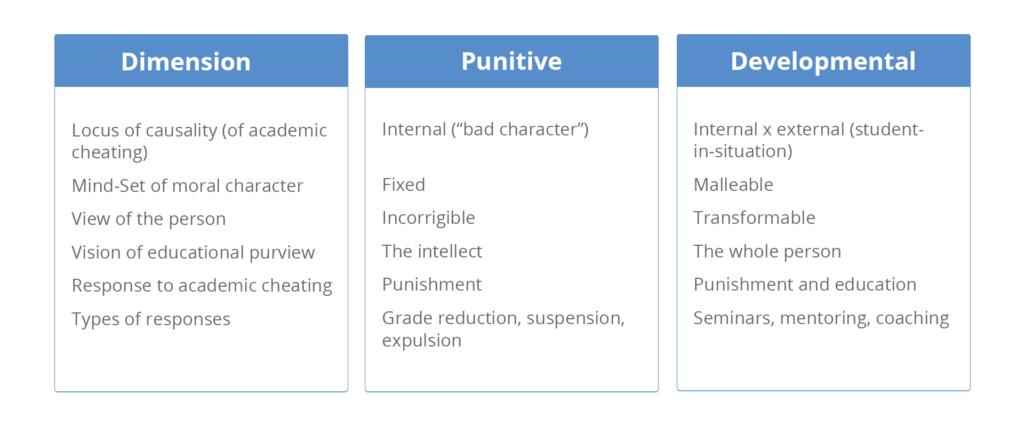

She then outlines very clearly the differences between a punitive bias and a development frame.

Responding to Academic Misconduct: Presuppositions of Two Contrasting Approaches

You can see from the table that punishment is included in both approaches, lest you think there are no repercussions to cheating, but in the punitive there is little opportunity for change or learning.

At the end of this article she and her colleague, Jason Stephens, devised a call to action for institutions:

In this article, we examined why educational institutions fail to respond developmentally to cheating, choosing instead a punitive approach. We also examined the benefits and limits of both punishment and development.

In the end, we argue that when educational institutions adopt a punitive approach, they are declaring that students who cheat are simply incorrigible and incapable of learning and growth, or we are incapable of helping them learn from cheating, and so all that remains to do is punish.

We believe that we can do more than this. We believe that we must do more than this. This article, is a call-to-action, a challenge issued to all colleges and universities, but particularly those who are already dedicating resources to other activities that facilitate character or moral development (like service learning or ethics classes), to make the commitment to move away from the punitive toward more developmental approach examples for responding to cheating.

To do this, institutions can start small, perhaps by training a small group of people to have structured reflection conversations with students to help the students do their own assessment and begin their own education.

For those institutions interested and able to do more, perhaps consider a restorative justice process instead of the current judicial process or using existing resources on campus (like the writing or learning center) to create educational opportunities that students could take after an instance of cheating.

To go further, institutions can form a taskforce to analyze their current punitive approach, discuss and design a developmental approach, and then invest some resources into building up the structures necessary to support students in the aftermath of cheating.

These same structures and resources can also engage in preventative education and culture-building, so the institution is supporting integrity in all facets, but the goal of moving from punitive to developmental should be primary.

If we refuse to help our students learn from their failures—ethical or otherwise—we are failing our students and falling short of achieving our educational missions.

Online proctoring with a human touch to protect academic integrity

Honorlock’s mission is much more than catching cheating and delivers a better way to protect academic integrity with online proctoring that’s good for the institution and for students.

Our exam proctoring services aim to protect academic integrity and empower students. We take the online proctoring experience and make it human by combining the benefits of live human proctoring backed by smart AI proctoring software.

Honorlock’s philosophies as a company follow the developmental approach rather than the punitive, which is why we are sharing this paper. We value integrity, humanity, humility and courage – for ourselves and in our relationships with others.

Our remote proctors are trained specifically on how to de-escalate the stress that goes with online proctoring so students can have a more human interaction with proctoring. Customers are able to adjust the online proctoring to more closely match their needs.

Our approach to the fine tuning of the AI that drives the online proctoring experience includes feedback loops so the product is constantly improving. Honorlock’s customers will attest to our focus on continually building online proctoring solutions and relationships that provide insight into a better solution for institutions and students alike.

The pandemic isn’t over yet

COVID is a hard lesson that’s still being learned. We aren’t going “back to normal” as we knew it. But with communication, perseverance and the strength of our communities and colleagues, we are making our way through it.

Please consider adding a look at what your institution’s practices and philosophies are in terms of cheating. If we are building a better model, perhaps it is time to include a change of direction in how integrity is approached, communicated and strengthened. Continue to be aware that different constituencies experienced the pandemic in different ways.

Here are some helpful Do’s and Don’ts we compiled that remind us of that humanity in learning.8

Don’t

- Do not forget that we are still in a pandemic. Do not forget that it is also an inequitable pandemic.

- Do not cause further harm. Do not support, enable, or endorse policies that perpetuate further inequities or fuel negative perceptions of students.

- Do not ask students for their approval of a decision that has already been made. Instead, engage with them in advance to help determine a solution.

- Do not require more proof of learning in an online class than you would normally require in a face-to-face setting.

- Do not forget that this is not the educational experience students wanted or expected. Nor is it a test of online education. And in case you were wondering, it still will not be “online education” in the fall. It will continue to be a derivative of emergency remote teaching and learning.

Do

- Use learning outcomes as a guide and means to design and focus educational offerings.

- Listen to students’ voices and respond accordingly.

- Modify assignments and assessments in ways that are flexible, use low bandwidth, and are based on the principles of equitable assessment.

- Be aware of and address systemic inequities.

- Engage in trauma-informed and healing-centered pedagogy and assessment

To learn more about how Honorlock can help your institution protect academic integrity and support students, sign up for a demo today!

Sign up below to receive more resources for tips, best practices, white papers, and industry trends

Smalley, A., Higher Education Response to Coronavirus (COVID-19), National Conference of State Legislatures, Mar 22, 2021, https://www.ncsl.org/research/education/higher-education-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19.aspx

2 Johnson Hess, A. How coronavirus dramatically changed college for over 14 million students, CNBC, Mar 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/26/how-coronavirus-changed-college-for-over-14-million-students.html

3McMurtrie, B., Good Grades, Stressed Students, Chronicle of Higher Education, Mar. 17, 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/26/how-coronavirus-changed-college-for-over-14-million-students.html

4Sedmak, T., Community Colleges, For-Profit and Rural Institutions, Black Undergraduates, and Male Undergraduates Suffered Most from Online-Only 2020 Summer Sessions, According to Latest Enrollment Data, National Student Clearinghouse, Sep 2020, https://www.studentclearinghouse.org/blog/community-colleges-for-profit-and-rural-institutions-black-undergraduates-and-male-undergraduates-suffered-most-from-online-only-2020-summer-sessions-according-to-latest-enrollment-data/

5Luna-Bazaldua, D., Liberman, J., Levin, V. “Moving high-stakes exams online: Five points to consider”, Education for Global Development, July 2020.

6Piercy, J., This Week at UC San Diego, Does Remote Instruction Make Cheating Easier, July 2020, https://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/feature/does-remote-instruction-make-cheating-easier

7Tricia Bertram Gallant & Jason M. Stephens (2020) Punishment Is Not Enough: The Moral Imperative of Responding to Cheating With a Developmental Approach, Journal of College and Character, 21:2, 57-66, https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2020.1741395.

8 Supiano, B., Teaching: Assessment in a Continuing Pandemic, https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/teaching/2020-08-20 3/6